No Sex Without Context: A Q&A with Sarah Richardson on “Sex Contextualism”

By Heather Shattuck-Heidorn and Kelsey Ichikawa

“We can make choices to use terms with care and in a manner that reduces harm. This opens up a space of deliberation — and of responsibility. ”

Recently lab director Sarah Richardson published a new paper in the journal Philosophy, Theory, and Practice in Biology, proposing sex contextualism as a new model for conceptualizing and operationalizing sex in biomedical research. What is sex, after all, in biomedical practice? In this theory-building work, Richardson takes us on a fascinating tour of how sex is actually being conceptualized within biological research. From the world of organs on chips to the development of estrogen shots for battlefield trauma, Richardson demonstrates that sex, as currently utilized in biomedical research, is far from a binary category of male/female. In laboratory practice, just as in lived biology, sex is a complex, multifaceted, and contextualized variable, in which different aspects of biological sex become differently relevant at different times, depending on questions, populations, and analytical strategies.

This contextual stance, of course, is in stark contrast to the bimodal, flat conception of sex often employed by “sex as a biological variable” (SABV) advocates, encapsulated by mantras such as “every cell has a sex.” In brief, policy mandates related to SABV frequently instruct researchers, largely without regard to question, to include both female and male cellular material or animals and to then analyze for sex differences, on the premise that binary sex is a deep, thoroughgoing aspect of biology that cuts across organisms, systems, and analytical issues.

Here, Heather took a moment to unpack sex contextualism with Sarah, to dig into both the substance and the implications of her argument.

Heather:

One of the first major contributions of this piece, in my opinion, is that you cohesively describe how the SABV policy conceptualizes sex — you have some really great quotes in the piece from SABV advocates, like “I don’t know what the question is but the answer is sex!” I am continually somewhat astounded at the relatively meteoric rise of this idea of sex; for instance, to go from the concept that “every cell has a sex” first being strongly articulated in 2001, to the premier of the journal Biology of Sex Differences in 2010 and the roll-out of the NIH mandate in 2016. And this has had results — according to one Canadian study of health funding proposals, the inclusion of sex as a research variable has increased from 22% to 83% over the last decade. Can you speak a little to why you think this idea has been so persuasive among certain sectors of both scientific researchers and regulators/funders, and how you see sex contextualism intervening or stepping into that arena?

Sarah:

“Sex as a Biological Variable” policies are intended to redress a history of androcentrism in preclinical laboratory research — that is, the use of biological materials primarily from male organisms. By doing so, advocates hope to capture sex-related variability that may be relevant in the understanding of disease and in the development of drug therapies. The problem is, as you say, that the implementation of the SABV policy has committed itself to a static, binary definition of sex, taking the form of mandated disaggregation and comparison of data by male/female sex, requiring a binary biological essentialist conception of sex at every level of biological analysis, regardless of context. Many critics of the policy, including you and I, have pointed out the problems with this approach. But advocates of SABV policies have largely ignored these critiques, dismissing critics as failing to appreciate the importance of sex, or even as denying that there are sex differences.

I wrote this article to positively articulate, in a concise, accessible, teachable format, an alternative framework to binary sex essentialism to guide research design and policy discussions, including those at major institutional funders of research such as the NIH and at the level of journal editorial policies. With “Sex Contextualism,” I aim to make clear, rather, that the substance of the debate about SABV among scholars deeply invested in science at the nexus of gender, sex, medicine, and biology lies in disagreement over just what sex is as a biological variable. Critics of SABV policies are sex contextualists. They aren’t against the study of sex-related variables; rather, they strongly disagree that sex-related variables are omnirelevant to every research question and that binary essentialist sex comparisons are necessary or sufficient to analyze sex-related variation.

Heather:

This view of sex as an omnipresent, omnirelevant, simple male/female binary raises a philosophically tantalizing question right at the intersection of philosophy of biology, metaphysics, and feminist philosophy: When should we attribute the parts of an organism — organs, tissues, cells — the same qualities as the whole individual? And, if a cell can have a sex, what, precisely, is sex? Can you dig into this emerging philosophical issue a little for us?

Sarah:

Yes, the mantra that “Every cell has a sex,” has been central in the SABV literature, and I think it’s very revealing of the undertheorization of just what sex is in the recent push for mandating sex-disaggregated analysis in preclinical research. Thinking through the question of whether the HeLa cell line, infamously derived without consent from Henrietta Lacks’ cervix in 1950 and then fused with mouse cells as well as the genomes of viruses and researchers who have handled the cell line, “has a sex” is actually a useful exercise for radically exploding and problematizing sex as a biological variable. The more one thinks about that question, the wilder “sex” becomes.

Just as in earlier work, where I analyzed whether genomes can “have a sex,” I take a skeptical eye to the view that the attribution of male and female can and should be extended to biological materials. Too often throughout history, whether brains, skulls, skeletons, or hormones, this has led to sloppy and imprecise thinking. Empirically, while it is certainly true that most biological tissues will bear traces of sex-related factors such that they may be said to be “sexed” or to “have a sex,” the mere presence of such factors may have little to do with phenotypic sex. That is, sex may be omnipresent in biological materials of sexually reproducing species — but it is not necessarily omnirelevant to our research questions, nor is the sex of biological materials such as cells likely to be most precisely characterized by the binary of “male” and “female.”

“The substance of the debate about SABV among scholars . . . lies in disagreement over just what sex is as a biological variable.”

Heather:

In the piece, after outlining the current approach to SABV, you use several really compelling case studies to explore how sex is being theorized and operationalized in practice. For instance, you talk about the fascinating example of organs-on-chips, or the way that estrogen may be on the way to being used as a battlefield drug to prevent sepsis, and how studies operationalized multiple sex-types among mice based on estrogen status. I wonder if you can talk a little, in lay terms, about how you see researchers operationalizing and considering sex in the the laboratory, and how you went about choosing the examples you have in this piece?

Sarah:

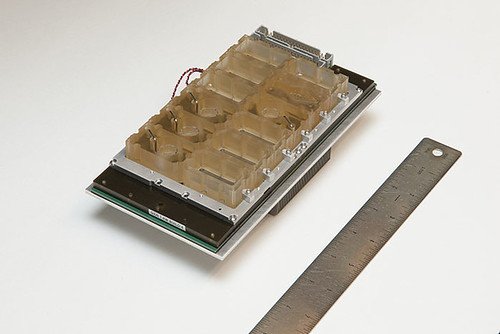

The EVATAR microchip models the female reproductive tract for testing sex differences in drug metabolism.

"EVATAR Chip" by National Institutes of Health (NIH) is marked with CC BY-NC 2.0.

When people first think about sex as a biological variable, they often picture a Vitriuvian man and woman, or maybe a little cartoon of a blue male mouse and a pink female mouse. I use extended examples in the article to move the reader into a different understanding of the material reality of biomedical research. When we talk about sex in laboratory-based experimental biomedical research — the sort of preclinical research that the NIH funds to the tune of $30 billion a year and that underpins our study of health and our process of drug discovery — we are talking about highly contrived experimental set-ups in the artifactual setting of the laboratory. Gonadectomized mice (mice with gonads removed) raised alone in cages; artificially inseminated cloned mice; tissues cultivated in fetal bovine media rich in pregnancy hormones; frozen or preserved biological samples; even, as in one of my examples, artificial systems assembled on a microchip. These are not oddities; these are the everyday human-constructed materialities that make for good, controlled experimental design in the laboratory. Sex-related variables appear in these materials, but operate in ways utterly specific to the experimental system. Appreciating this is critically important to thinking in a clear-eyed way about what it means to study and make reasonable inferences about “sex as a biological variable” in preclinical science.

Heather:

As we talk about how sex is conceptualized in these cases, it’s clear that you’re not somehow, as feminists are sometimes accused of, claiming that there is no biological material reality to a concept we are calling sex. But rather, that sex shifts according to the research context, as we will unpack more in a moment. I’m interested in how clear you are on this point, even saying at one point in the paper, “I stress that sex contextualism neither denies the reality of sex as an evolved developmental pathway with many implications for biology nor the possibility that male-female comparisons may at times be an apt research design for studying sex.” Can you speak a little to the tendency of reducing a feminist critique of sex essentialism to a stereotyped position of “these feminists deny the existence of sex as a material reality”? Did you feel you needed to be that explicit in order to not be read in that way?

Sarah:

There is a widespread misunderstanding that critics of sex essentialism simply do not believe that there are sex differences, that they regard any scientific work on sex as suspect and anti-feminist, that they do not understand the biology of sex, or that they are otherwise engaged in wishful thinking about the reality of the biology of sex, in the service of their political beliefs. My work has long argued for the need for the construct of sex in science; at the same time, it has argued for precision, rigor, and ethics in the use of that concept. I hope that the concept of sex contextualism helps clarify that the feminist critique of sex essentialism offers a different conceptual approach to operationalizing sex in biological research and is not a rejection of scientific study of sex-related variables.

Heather:

Ok, let’s talk about sex contextualism, which is really the heart of this paper. This is an alternative framework for how to consider and operationalize sex in the biosciences. In your words, sex contextualism is a pragmatic framework that “recognizes the pluralism and context-specificity of operationalizations of ‘sex’ across experimental laboratory research.” It acknowledges that no single component or set of components specifies sex across all biomedical research programs, and thus you “invite researchers to justify their choices in how they operationalize sex.” Those choices might be guided by things like observational constraints, characters or developmental stages of the particular strain or model being used, environmental variables, or practical aims, to name a few. You outline in the table below how this approach departs from sex essentialism.

Sex contextualism has explicit affinities with Sally Haslanger’s ameliorative approach to the concepts of “race” and “sex” in her essay, “Gender and race: (What) are they? (What) do we want them to be?” Could you unpack what it means to do ameliorative conceptual analysis? Who are the “we” who decide what we want sex to be in a given context?

Table reproduced from (Richardson 2022)

Sarah:

Conceptual work around sex, gender, and race in social ontology stands right on the boundary between doing descriptive and prescriptive work. On the one hand, the philosopher could simply conduct conceptual analysis to understand just what people mean, in particular contexts, when they use a concept such “race” (or sex). As it turns out, these terms are polysemic, meaning that people use them in many different ways. Then the question arises as to whether some of these uses should be preferred to others. If we engage with this question, then we’re in the business of evaluation and prescription. If our values are feminist, anti-racist ones, we might think some uses are better than others, perhaps because they prevent harms or open up new, liberatory options. This harm-reduction or liberation-affirming approach to conceptual analysis is “ameliorative.” Haslanger points out, however, that such work has pragmatic limits. One cannot change language by fiat. As feminists, we might think it ideal to do away with gendered pronouns, for instance. But uptake is not high for this at the present moment. Perhaps other ameliorative pronoun-affirming practices take priority. Similarly with sex (and male, female, man, and woman), these are terms that have folk meanings as well as highly technical meanings within particular areas of scientific expertise. For digametic sexual species (species in which sex determination results from two types of sex chromosomes), simply doing away with those concepts is not only unrealistic but, in many cases, may be undesirable, as it would reduce the ability to make reasonable inferences about the evolution and developmental biology of mating and reproductive systems across areas of scientific study. Nonetheless, “we” users of the concept of sex do have degrees of freedom about when and how we use sex-related concepts, and how we qualify and contextualize them. Within these degrees of freedom, we can make choices to use terms with care and in a manner that reduces harm. This opens up a space of deliberation — and of responsibility.

Check out our other resources on sex contextualism:

Recommended Citation

Shattuck-Heidorn, H. and Ichikawa, K. “No Sex Without Context: A Q&A with Sarah Richardson on ‘Sex Contextualism.’” GenderSci Blog. 2022 April 11. Accessed at: genderscilab.org/blog/q-and-a-sarah-richardson-on-sex-contextualism

Statement of Intellectual Labor

Questions created by Heather Shattuck-Heidorn with help from Kelsey Ichikawa, Marina DiMarco, and Mia Miyagi. Edits for clarity from KI, MD, HSH, and SR.