How did a small COVID-19 sex difference study with largely negative findings become framed as a "Battle of the Sexes"?

Authors: Jamie Marsella, Marion Boulicault, Helen Zhao, Annika Gompers

In August 2020, Nature published a study entitled “Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes.” While the study was small and found few statistically significant sex differences, its conclusions implied otherwise, recommending that future therapies and even vaccine distribution plans emphasize sex differences. Men, the authors suggested, might require vaccines and therapies that increase T cell immune response; women might require therapies that dampen innate immune response. Below we explore how the authors helped frame this small COVID-19 sex difference study as an unsubstantiated “Battle of the Sexes” in the popular press.

Public proliferation of unsubstantiated claims

As we demonstrate in our analysis in Nature (to be published on Wednesday) and accompanying blog post, Takahashi and colleagues’ findings show very few statistically significant sex differences in immune responses between men and women after adjustment for age and BMI. Yet most, if not all, media coverage of the study claimed that it provided evidence of large sex differences and a definitive explanation of why, in many contexts, men in aggregate are more likely to die from COVID-19 than women.

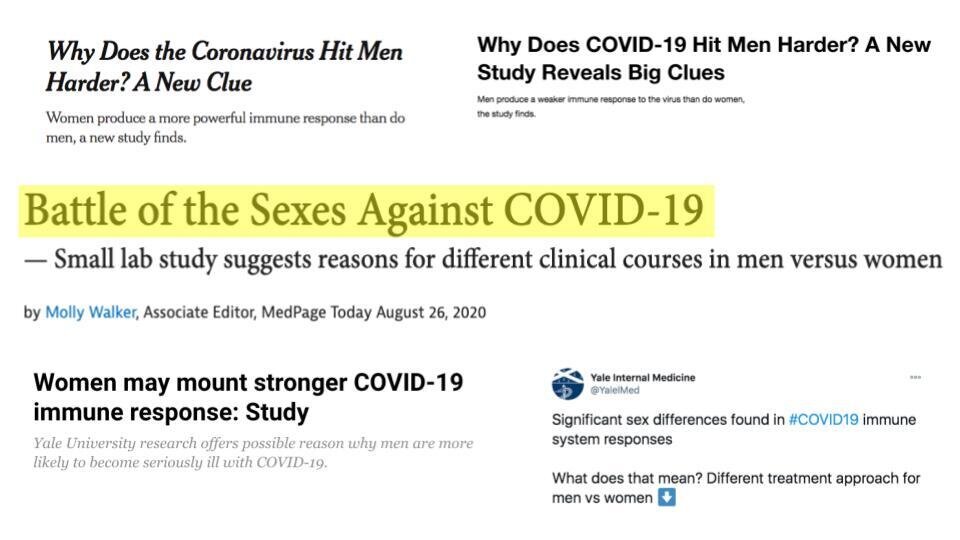

Framed as a “Battle of the Sexes Against COVID-19,” reporters cited the study as demonstrating sex differences in immune responses to the SARS-COV-2 virus. The New York Times reported that scientists had found that “men produce a weaker immune response to the virus than do women,” and that “men, particularly those over age 60, may need to depend more on vaccines to protect against the infection.” Media coverage amplified the study’s claim that it supports different vaccine regimens for men and women, writing that the study’s findings “imply that men and women need different treatments” (Aljazeera), and that sex-specific vaccine dosing should be considered (Vice).

Despite the study’s small sample size, minimal findings of sex differences, and observational nature, the study’s conclusions and treatment implications were frequently characterized as large in magnitude and as settled science. Media coverage presented the study as having “answered” questions and “found” significant sex differences.

How was it possible for these misrepresentations to gain traction?

How did these misrepresentations and inaccuracies gain traction? Part of the responsibility lies with the scientists and scientific institutions behind the study. In their public communications, lead investigators provided unsubstantiated claims that the media then promoted. In a Yale press release, Dr. Iwasaki stated that her team’s data “suggest we need different strategies to ensure that treatments and vaccines are equally effective for both women and men.” In an accompanying video on the same page, Dr. Iwasaki elaborated, “This study highlights the importance of thinking about sex as a determinant in various infectious diseases, and it is a lesson for all of us to be paying more attention to improved patient treatment regiments based on sex differences.” These quotes are featured in each of the news stories discussed above. In the same press release, Carolyn Mazure, the Director of Women’s Health Research at Yale, pronounced that “These findings answer questions about COVID-19 that point the way toward a more effective, targeted response to this disease... [R]esearchers racing to develop treatments and vaccines should consider separate strategies for women and men so that everyone can benefit'' (Yale). On the official Twitter account for the Department of Internal Medicine at Yale School of Medicine, a post reads: “Significant sex differences found in #COVID19 immune system responses. What does that mean? Different treatment approach for men vs women.”

The authors misrepresented their work by offering reporters additional conclusions that were not supported by the study’s findings. Dr. Iwasaki told the New York Times that women may have better outcomes if given a drug to “blunt” certain proteins, despite the fact that this claim was not a finding of the study. Another author further speculated in the same article, “You could imagine scenarios where a single shot of a vaccine might be sufficient in young individuals or maybe young women, while older men might need to have three shots of vaccine.” The New York Times article is one of many high-profile pieces in which the authors boldly promoted the prescription, which they portrayed as based on the study’s findings, that medical practitioners should consider different COVID-19 treatment and vaccination protocols for men and women.

These interpretations of Takahashi et al.’s findings capitalize on the popular belief that biological sex is the primary factor underlying differences in health outcomes between men and women. This belief, known as “sex essentialism,” is pervasive in popular accounts of male and female sex differences, obscuring the social structures that enforce gendered roles, behavior, occupational segregation, and other structural gendered factors that contribute to the differential distribution of traits across sexes. Sex essentialist premises are a problem both scientifically and ethically: they set up research that reinforces sexist stereotypes, and they lead to the exclusion of relevant data that documents how gender and sex are contextual and co-constitutive. Sex essentialism provides a a simplistic and familiar, if deeply inaccurate, explanation for observed differences, and may have facilitated the ready uptake of Takahashi et al.’s purported conclusions.

“The unsubstantiated nature of these claims, however, is harmful, both in the clinic and in perpetuating sex essentialism”

Some feminists, concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on women, also latched onto Takahashi et al.’s study. An article in Ms. Magazine highlighted the study, asking, “Is sex discrimination in medical research thwarting a cure for COVID?” The author, Lori Andrews, states, “The fact that, in 2020, researchers would blindly assume women’s bodies behave like men’s is troubling.” She cites Takahashi et al.’s research as an exemplar of women-led science “challenging the male-centric approach.” Andrews reiterates the author’s claims about the role of biological sex differences in COVID-19 without any critical discussion or contextualization of this small study’s minimal sex difference findings.

The popular media articles we’ve discussed intend to inform, engage, and entertain their readership. The Takahashi et al. paper provides exciting and provocative conclusions that relate to important aspects of the trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic. The unsubstantiated nature of these claims, however, is harmful, both in the clinic and in perpetuating sex essentialism as a foundational premise in scientific research. As experts with authority, researchers have a responsibility to accurately represent their own work. The authors should have been more cautious in conveying the strength and magnitude of their findings of sex differences and in proposing, both in interviews with media and in their article itself, an unproven and speculative strategy for sex-dependent vaccination and treatment -- especially given the potential harms of promoting sex essentialism.

Recommended Citation:

Marsella, J., Boulicault, M., Zhao, H., and Gompers, A. “How did a small COVID-19 sex difference study with largely negative findings become framed as a ‘Battle of the Sexes’?” 2021 Sept. 20. GenderSci Blog. genderscilab.org/blog/nature-matters-arising-media-analysis

Statement of intellectual labor:

Jamie Marsella contributed to the initial planning and draft of the blog post, and integrated lab member comments and edits during the revision process. Marion Boulicault, Helen Zhao and Annika Gompers contributed to the conceptualization, drafting and editing of the blog post. Sarah Richardson and Meredith Reiches provided conceptual and framing comments and edits.